Touring Earth’s Impact Craters

Wednesday, 17th March 2010 by Chris Hannigan

Looking up at the moon, one of the most striking visible features has to be the sheer number of impact craters around its surface. These giant holes in the ground are made by asteroids and comets flying through space and then crashing into our little satellite.

Of course many of these are easy to see without any special equipment, so for many years scientists on Earth wondered if we can see them all so easy up there, why can't we see them down here on our planet? Then along came aerial photography…

GSS visited some of the most recognizable impact craters on Earth already, including Barringer Meteor Crater in the United States and Manicouagan Impact Crater in Canada, but updated and enhanced imagery makes these sites worth a second visit.

We start our tour with the largest verified impact crater on Earth, Vredefort Crater in South Africa. Measuring a staggering 250 - 300 km (155 - 186 miles) across, this crater was formed over 2 billion years ago by an asteroid estimated 10 km (6 miles) in size.

Today, the most recognizable feature of the crater is the northwest rim that created the mountains near the town of Parys. Vredefort was also added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 2005.

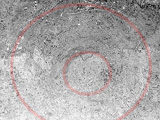

Our next stop is a crater in Northern Ontario, Canada near the city of Sudbury. The Sudbury Basin was formed by a meteorite impact 1.85 billion years ago, creating a round 250-km (155 miles) crater.

Subsequent geological processes like tectonic plate movement then stretched into its current oval shape, which is hard to see on the satellite image. However, the crater shape is strikingly obvious when using Google's terrain mapping. It is the second largest verified impact site on the planet.

Perhaps the most famous meteorite impact of them all is the one that slammed the Earth in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, and also is the one that scientists believed killed 75% of the species on Earth including the dinosaurs1.

About 65 million years ago, a 10 km (6 mi) wide meteorite slammed into the Earth and created a 180 km (110 mi) wide crater centered just off the coast of present day Mexico in the Gulf of Mexico. Today, the south to southeast rim can still seen with Google's satellite maps if you know where to look. The Chicxulub crater is the third largest verified impact crater on the planet.

Be sure to check out the other GSS articles on impact craters and other natural landmarks, including the Kebira Crater. Check Wikipedia for more information about the Vredefort Crater, Sudbury Basin, or the Chicxulub Crater. Since there are so many sites around the Earth, we'll be sure to have more crater articles soon!

-

Although the debate rages on about what caused the extinction of the dinosaurs, the astroid impact theory was recently deemed the most likely. ↩︎

I live on north Alabama and always see this feature on the weather on TV and have wondered if it’s the remnants of a meteorite crater:

View Placemark

Hi Don,

Surely your not talking about Talladega? 😛

Seriously though the only thing I could find in the area is a crater further south in Alabama called the Wetumpka Crater.

https://www.googlesightseeing.com/maps?p=&c=&t=h&hl=en&ll=32.524816,-86.175385&z=12

I’m not sure if this is what your pointing to, but it’s just northeast of Montgomery between I-65 and I-85. Here’s some more information for you about this site:

http://www.unb.ca/passc/ImpactDatabase/images/wetumpka.htm

Hi, Don. I’ve long wondered about the same geological feature of which you speak. It’s a large, whitish crescent that arcs thru eastern Mississippi and west central Alabama. It’s definitely circular, so it looks like the remnants of a crater. I can’t find anything about it, so I’ll probably have to find a geologist to ask.

Here’s the feature that I (and Don H.) describe: View Placemark

What I’m talking about is the large light colored arc in the left side going from about 10:00 to 5:00.

Very interesting. But it appears that a lot of the coloration comes from cultivated land. But maybe that’s just a side effect?

Take a look at western borders of Czech Republic – do you see ring of montains?

The Carolina bays – not one crater, but one event. Clicky here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carolina_Bay

The Carolina Bays are interesting for sure. Check out this article from 2008…

https://www.googlesightseeing.com/2008/05/30/the-mystery-of-the-carolina-bays/

Sudbury is actually in Northern Ontario. The dividing boundary is along the French and Mattawa Rivers and Lake Nipissing near North Bay. Everything north and west of that point is “the north” and that includes Sudbury. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_Ontario

Hi Derek,

Thanks for the information. I’ve updated the post with the correct location.

So, if the dinousaurs were extincted because of a meteorite, other life forms were not, since we’re alive now today. But what if another one strikes? Is it possible to predict such an impact? And if yes, what measures should be taken?

What happens to the meteor? Does it just break up or become inbedded in the much larger crater it creates?

Ioana, yes it is possible to predict when we may get hit again, but as far as I know, not very far into the future (statisticly we’re overdue for another strike). As for measures to be taken, if it’s the size of the one that made the Chicxulub crater and it hits us, then not much, they’re not called slate wipers for nothing. Although one idea is to use nuclear weapons to either distroy the meteor or knock it off course so it misses

This arcs thru eastern Mississippi and west central Alabama is probably geological structure- look at this map: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:North_America_Geological_Tapestry.gif

Thanks. Looks like your map explains the arc that I was wondering about. Now I’m going to look for some more detailed maps of the area.

Wow! Check this out. The crescent is quite visible here: http://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/home_maps/images/phosphorus_streams.png

…and one more map that helps clarify the reason for the geological features of the southeastern U.S.: http://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/b2016/chapc/chc3.gif