Mauna Loa: The World’s Largest Volcano

Tuesday, 8th November 2011 by Kyle Kusch

Hardcore Google Sightseeing readers may remember all the way back to 2005 and the third month of the site when we looked at the volcanoes of the Big Island of Hawaii. With the wealth of new hi-res satellite and Street View imagery over the past few years, it’s time to return to the Big Island and explore the world’s largest volcano.

Covering an astounding 5,200 km2 (2,000 sq. mi.) Mauna Loa is not only the world’s largest volcano, but is actually the largest mountain by area and by volume on the planet. In fact, when measured from its ocean base, it’s actually higher than Mount Everest! (Update, see this comment for some clarification on this point.)

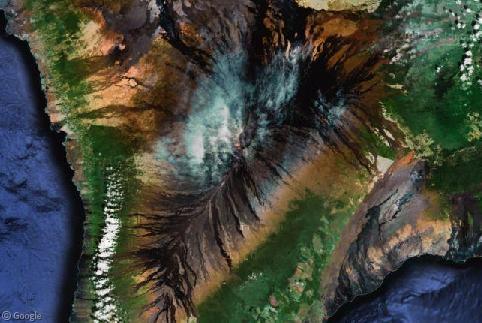

Mauna Loa has been in a constant state of eruption for the past 700,000 years. Its massive size is due to its nature as a shield volcano; rather than exploding out of the volcano, the lava flows down the sides of the mountain just like rivers, slowly building the mountain higher and higher over time. From above they almost look like army camouflage or an impressionist painting. Some of these old channels are so huge that they cover hundreds of square kilometres as they run all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

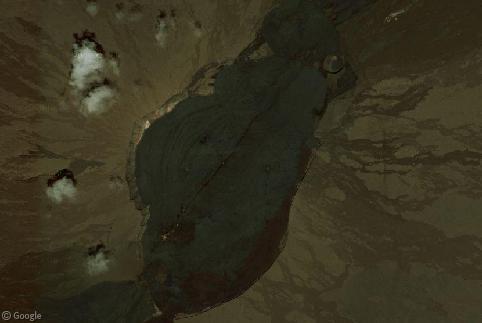

Eruptions occur all over Mauna Loa in a rift zone several kilometres long. The summit crater, Mokuʻāweoweo, hasn’t actually erupted since 1984. This has allowed the lava that fills the massive 4.8 x 2.4 km (3 x 1.5 mile) crater to solidify on top, although one can still make out the conduits and fissures from where the lava emerged and probably will again.

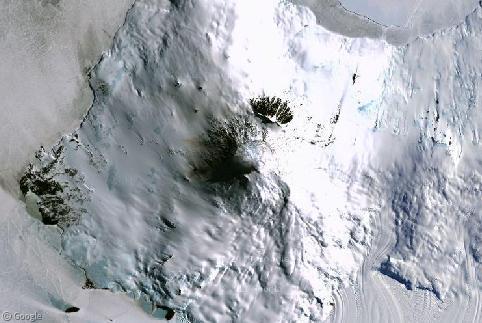

Moving further down the rift zone to the southwest, molten-hot lava can be seen erupting out of cinder cones and slowly making its way down the slopes.

Because of the constant streams of new volcanic materials being laid down, much of the slopes are covered in nearly-barren brown and black volcanic rock. Some of this rock is smooth and pillowy, produced by flows known as pāhoehoe, while much of the slopes are covered in jagged, loose and blocky rocks produced by ʻaʻā flows. Despite the rough terrain and near-desert conditions in places, that hasn’t stopped people from building houses directly on top of the blocky old lava channels.

Mauna Loa is also famous as a major centre of scientific research, as the US government operates both a solar observatory and an atmospheric observatory on its slopes near the summit to take advantage of the high altitude and clear air.

Rough and narrow, the road up to the observatories pushes through seemingly endless fields of jagged rock as it climbs up the volcano. Along the way, drivers get an excellent view of the neighbouring volcano of Hualālai in the distance before reaching the observatories at the end of the road.

Since the last major eruption in 1984, Mauna Loa has been rather quiet; the longest recorded quiet period in its history. It’s only a matter of time before another big blast comes along and once again changes the landscape of Hawaii’s Big Island, and with over 100,000 people potentially in its path, you’ll be sure to hear about it when it does.

The “load placemarks in google earth” link doesn’t seem to be working for this one.

Thanks Mickey, we will investigate.

Cool, thanks. I’d rather just fire up that KML than have to find all of those places individually. 🙂

Micky, I’ve found all the missing placemarks – can you try again?

Thanks!

Yep, it works great now. Thanks!

I’m a bit confused about your “molten hot lava” images. GoogleEarth (unless you have it set to historical overlays) always displays the latest satellite imagery, and there definitely aren’t any active lava flows or craters on Mauna Loa right now. Clicking on those images also links you to the current topography – not a glowing flow in sight.

If these are historical images, some citations and dates for them would be nice.

Hi, Jessica,

This entry was originally written back in August for Volcano Week 6. At the time, this was the imagery on Google Earth.. Google updated their imagery on Mauna Loa in September. These things happen from time to time, since Google are always updating their imagery, as you’ll find with many of the older entries on the site. This one just happened to catch us out by a month instead of a year or two.

Interesting that the images were there at all! Must have been some sort of slip-up on their part, since the last eruption was in 1984 and the only way to show anything molten in those scenes would have been to use pretty old satellite images.

Apologies Kyle (and Jessica), as Kyle said the article was originally written in August, and when I came to post it I failed to notice the imagery had already been updated! Not often that happens 🙂

Also a bit concerned about that Everest comparison: if you stick a flea on top of a 20′ column and an elephant on top of a 5′ one, you can make out by the same measure that the flea is taller than the elephant. Once you use a common reference point (for your convenience the bottom of the ocean floor Hawaii stands on) not only does Everest once more become the taller of the two, but you’re forced to add in the entire Eurasian landmass, and possibly Africa as well because that floor is deeper than the Suez canal, which again demolishes the mass argument!

Hi Rahere,

One thing we’ve learned here on Google Sightseeing over the years is that any claim to be the “world’s largest/tallest/heaviest/longest/etc” could always be manipulated by the frame of reference.

So readers aren’t confused, I’ve added a link to your comment from the article.

Indeed, one can get caught in tons of arguments based on technicalities.

In this case, the ‘base’ one measure from would be the structural bottom of the mountain. In this definition, in Everest’s case, you would be measuring from the surrounding continent, while in Mauna Loa’s case, it would be measured from the ocean floor itself. None of Everest structurally lies below sea level, while much of Mauna Loa does. A ‘common reference point’ wouldn’t apply in this case since they’re beginning at two different types of bases.

That said, I see Rahere’s point, since things can get very technical once you begin incorporating various definitions. Using the most technical of arguments, Chimborazo would the ‘highest’ mountain since it sticks out further into the atmosphere than any other mountain as it sits near the Equator, but it couldn’t be the ‘tallest’ since the base from which it starts is much higher.