The Crowsnest Pass

Wednesday, 20th February 2013 by Kyle Kusch

In a country known for its mountain scenery, the Crowsnest Pass corridor shared between British Columbia and Alberta stands out as one of Canada’s most scenic mountain destinations. The pass is also known for being one of the world’s largest sources of coal and for the numerous tragedies that have shaped its landscape over the past 125 years.

At an elevation of 1,358 m (4,455 ft), the Crowsnest sits on the drainage divide between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans and is the southernmost transportation route through the Canadian Rockies. In 1897, the Canadian Pacific Railway was built over the pass and almost immediately thousands of people flooded into the mountain valleys on either side of the pass looking to find their riches through coal. In a 15-year span between 1902 and 1917, over 400 miners died in various catastrophic mine disasters.

The pass forms the border between the provinces of British Columbia and Alberta. Sitting on the top of the pass is the appropriately-named Inn on the Border. The border splits the main building in two – the kitchen lies in Alberta, while the dining room lies in British Columbia.

Four separate glacier-fed lakes lie at the top of the pass. Here, the Crowsnest Highway divides Island Lake in half as it enters Alberta.

When the railway came, numerous mining operations large and small were formed, each with its own company town to house its residents. One of those towns was the sleepy village of Frank, Alberta. The village sits to the north of Turtle Mountain, the mountain its residents mined. Topped with weak limestone, the removal of the underlying coal accelerated the slumping of the mountainside that had been occurring for thousands of years.

At 4:10am on 29 April 1903, a 30 million cubic metre (1 billion ft3) block of Turtle Mountain collapsed, sending a plume of rock and mud racing toward Frank at a speed of about 70 km/h (120 mph), wiping out the eastern portion of the town and burying between 70 and 90 people in their sleep. The exact number of dead remains unknown as only 12 bodies were ever recovered; the rest still lay somewhere in the rubble.

More than a century later, the scar of the Frank Slide defines Turtle Mountain, and limestone boulders still cover thousands of acres of the valley. The railway and highway were rebuilt through the middle of the debris, and eventually the Frank Slide became one of Alberta’s major tourist attractions. Today, more than 100,000 visitors per year visit the slide.

Another unlikely attraction on the Albertan side is this old cafe in the hamlet of Bellevue. In 1920, a group of miners got word that the wealthy bootlegger Emilio Picariello would be aboard a train coming through the pass and decided to rob the train. Picariello was nowhere to be found, but the miners made off with passengers’ money nevertheless. Five days later, two of the miners were spotted inside the Bellevue Cafe by police, and a shootout erupted. One of the miners and two constables were killed. The other miner slipped away wounded and escaped into the rubble of the Frank Slide a few minutes to the west, only to be captured four days later in a nearby town.

While coal mining on the Albertan side of the pass ended decades ago, the coal operations at Elkford and Sparwood, British Columbia are some of the largest on the planet, covering hundreds of square kilometres.

Sparwood, a town of 4,200 people, is barely visible in the centre-left of the following image, dwarfed by the massive mine to the east.

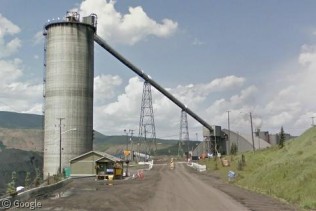

Street View can’t take you right inside the mines (yet), it does drive right up to the entrance of the big mine at Elkford, where we see a massive wash plant and tailings pile.

Sparwood’s largest tourist attraction is the Terex Titan, which sits in its own park at the entrance to town. Built for hauling up to 320 tonnes of coal, it was the largest truck in the world when it was built in 1973, weighing 231,100 kg (509,500 lbs) and standing 6.88 m (22 ft 7 in) high.1

At the west end of the Crowsnest corridor is the city of Fernie. Destroyed by fire five times between 1902 and 1908, Fernie’s central business district was rebuilt the fifth time using brick and stone. Today, the buildings remain almost exactly as they were in 1908.

Fernie is also home to Fernie Alpine Resort, which receives some of the largest snowfalls of any ski resort in North America. The resort is known for its deep powder and panoramic vistas. Best of all, the entire resort is now available in Google Street View, so you can sit back at your computer and take it all in – perhaps while enjoying a nice Currie Bowl.

-

Longtime readers will remember that we visited the Terex Titan way back in November 2008 (although not nearly as up-close). ↩︎

Great article…thanks for posting!

Would you believe that just last weekend I added Frank Slide to my ‘list of locations to consider writing about someday’!

Glad you were able to work it into an epic post, Kyle – far better than I would have done!

Might not be the same Ian Brown, but you went on a food tour of Canada a couple of years ago and we urged you to come through the mountains on the southern route. You went through Banff instead and were disappointed with the fare. If you ever come through the Frank Slide, eat with us at Stone’s Throw Cafe…you won’t be sorry you did. 🙂

Sorry, not the same Ian Brown (of the Globe), though I suspect a significant portion of my Twitter followers think I am him!

Thanks, Ian! Although I’m sure you would have done a great job with it as usual!

Just clicked on the Stone’s Throw website. SOOOO hungry now. Going to be thinking about cheesecake-stuffed strawberries all day. Only 5 1/2 hours away, too…